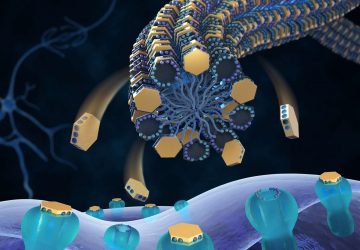

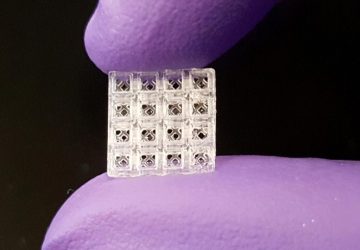

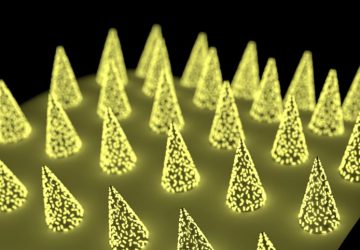

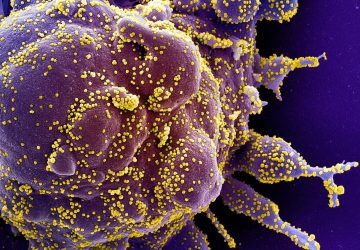

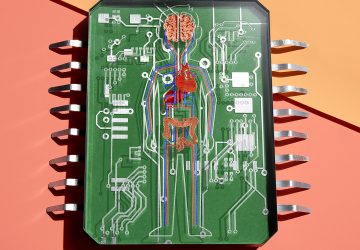

The field of tissue engineering has advanced to the point where bioengineers can use 3D printing to grow human tissues like bone and muscle. But these structures often lack the complexity of real human tissues. So scientists at the University of California in San Francisco are trying a different method: They’re recreating early development, then leaving it up to cells to fold themselves into the necessary structures.

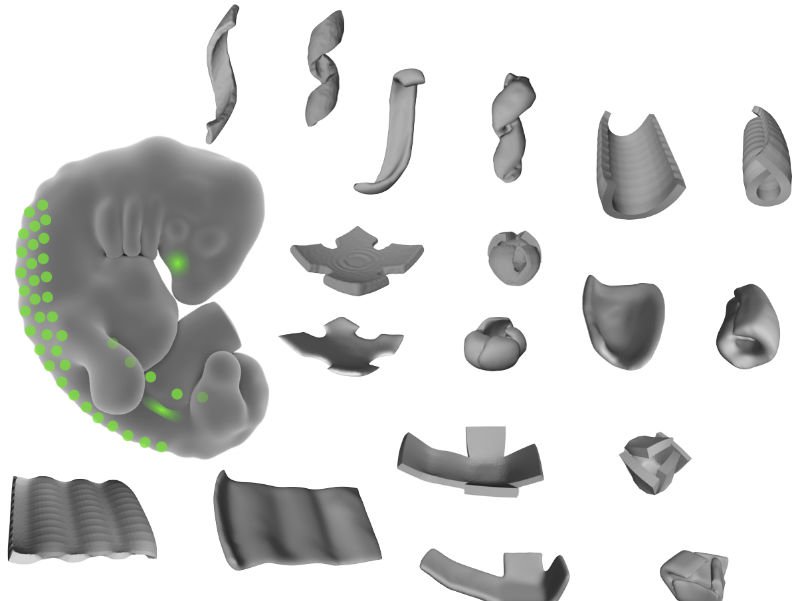

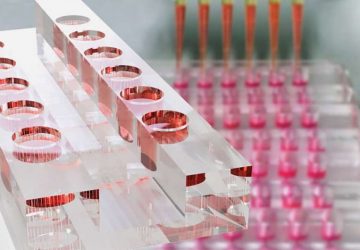

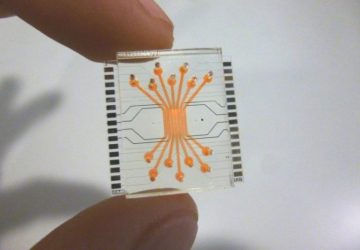

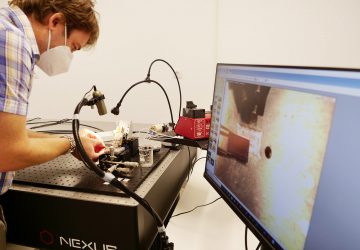

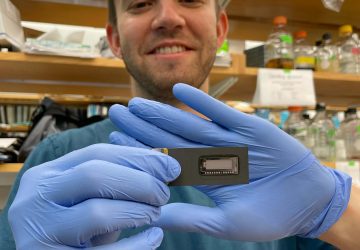

Reporting in the journal Developmental Cell, the scientists explain that they start by taking active mouse or human cells and patterning them to thin layers of matrix fibers. The technology, called DNA-programmed assembly of cells (DPAC), results in a cellular template that folds itself into complex bowls, coils and ripples. The cells collaborate to make the tissues in a manner that closely resembles natural development, they said in a statement from UCSF.

“We’re beginning to see that it’s possible to break down natural developmental processes into engineering principles that we can then repurpose to build and understand tissues,” said first author Alex Hughes, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at UCSF, in the statement.

RELATED: Duke engineers create fully functional beating heart patch

The UCSF research builds on advances made in the burgeoning fields of 3D printing and regenerative medicine. Over the past several months, scientists at Duke, Boston University and other institutions have reported progress in the effort to grow human heart tissue that may someday be able to be used to replace damaged cardiac muscle. Researchers at the University of Toronto are developing a tiny heart patch that they hope to be able to deliver via syringe.

More than 100 3D-printed medical devices are already on the market, made primarily from synthetic materials like titanium. But the FDA is expecting a flood of such products to come, including tissues and drugs made with 3D technologies—and the agency just took a big step toward helping usher those products to market. In December, the FDA released its first technical guidance for the manufacturing of 3D-printed medical products.

The UCSF researchers will further develop their DPAC technology by studying how cells change and differentiate during tissue folding. They also plan to combine the technique with other technologies that control how tissues form into patterns. In their journal article, they envisioned “a 4D process” that starts with a 3D structure but evolves over time into “more defined and life-like structural features.”

source: www.fiercebiotech.com