App by app and tool by tool, scientists are studying whether digital health interventions work, with mixed results

As digital health continues to explode on smartphones worldwide, researchers are digging in, trying to figure out which of the new offerings actually work. These scientists aim to determine, using top notch clinical trials, the effectiveness of medical apps, telemedicine and other kinds of digital therapeutics and diagnostics.

It’s a big task. The pace at which software developers are commercializing digital health tools surely exceeds the pace at which scientists can study them. The good news: Unlike traditional medicine, there’s no shortage of data in digital medicine.

Here, we give you three studies, all published this month, that illustrate the different ways scientists are putting digital health through the clinical trial wringer. The conclusions show just how messy and nuanced digital health research can get.

1. Meditation app no better than a sham app at improving critical thinking

After being passed down for thousands of years, the teaching of mindfulness meditation by live human instructors is starting to be replaced by digital apps.

Proponents say the practice of meditation, which involves bringing one’s focus to the present moment, can reduce stress, increase attention, and even improve cognitive function. But the latter of those claims are backed by very little evidence, says Chris Noone, a psychology researcher at the National University of Ireland, Galway.

Noone wanted to find out, with a rigorous study, whether the claims of cognitive benefits are true. The best way to do that, he felt, was to study people who practice mindfulness using an app.

“Apps are the most popular way people are learning mindfulness meditation,” he said in an interview with IEEE Spectrum. Plus, the digital aspects of apps offer experimental controls, such as being able to double blind the study and standardize the instruction—something that can’t be done with live instruction.

Noone chose the popular meditation app Headspace, which offers specific mindfulness meditation instruction, and boasts millions of users in more than 190 countries. He pitted it against the same app with fake meditation instruction developed for research purposes, which told users to simply close their eyes and breathe, says Noone.

Over 70 study participants were given a series of tests and questionnaires that score various cognitive functions such as critical thinking, open-minded thinking and memory. Then for six weeks, half of the participants used Headspace and the other half used the sham app.

After participants completed 30 meditation sessions, they took the cognitive tests again. Those who had used Headspace improved their test scores about the same amount as those who had used the sham, Noone and his collaborator Michael Hogan found. They concluded that there is no evidence that engaging in mindfulness meditation improves critical thinking performance.

The participants “probably just got better at taking the test,” says Noone. The study was published 5 April in the journal BMC Psychology.

2. Mobile app helps patients remember to take their blood pressure medication, but doesn’t improve their blood pressure

We aren’t very good at consistently taking our medication. That’s particularly true for people who must manage chronic conditions with drugs over long periods of time.

Lots of apps are being developed to help people adhere to their drug regimens. There are over 100 such apps for hypertension, or high blood pressure, alone. The question is: Do these apps work?

At least one does—a little bit—according to a study published 16 April in JAMA Internal Medicine. The authors asked more than 200 people to use smartphone software called Medication Adherence Improvement Support App for Engagement-Blood Pressure, or MedISAFE-BP. The app aims to help people with hypertension remember to take the meds, and includes reminder alerts, adherence reports and optional peer support.

After 12 weeks, the researchers saw a “small” increase in medication adherence among people using the app, compared with no change in a control group. Despite taking their medication more consistently, there was no improvement in systolic blood pressure compared with the control group, possibly due to fluctuations in home blood pressure readings, the authors conclude.

The study is the first to assess a hypertension medication adherence app as a stand-alone intervention in real-life settings, according to the report. Other smartphone adherence tools have been studied in clinic-based settings, or used to improve patient-doctor communication.

3. Telemedicine tool is as effective as an in-person exam at diagnosing rare cause of blindness in babies.

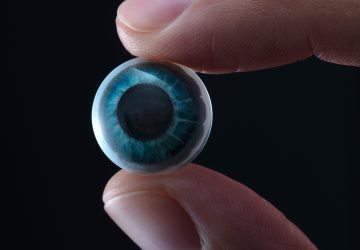

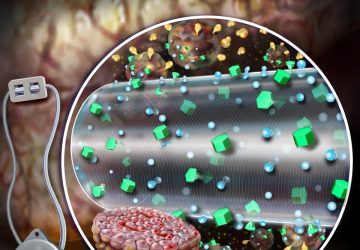

For more than a decade researchers have been studying whether it’s possible to accurately diagnose diseases of the retina using only a photograph of the eye. If an image is just as good as an in-person exam, the thinking goes, patients can seek opinion from the most highly skilled specialists without having to travel long distances.

The conclusion, after dozens of these studies, is yes: Images—the telemedicine version of the eye exam—are just as good as the live thing.

But virtually all of those past studies make the same troublesome assumption: that the in-person eye exam is the gold standard. “They assume that the exam done by an expert in an office gives you the correct answer,” Michael Chiang, a professor of ophthalmology and medical informatics at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, said in an interview with IEEE Spectrum. “But when you look at the photograph of the eye, there is photographic evidence that the clinical examiner made a mistake. It’s been a bit frustrating for me.”

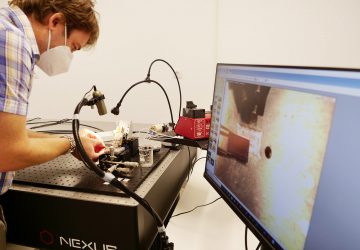

Chiang wanted to see how accurate telemedicine exams are when compared to an impartial gold standard. So he and his team created a new reference standard based on a majority vote system from a three-person panel of experts. “It was extremely painstaking to come up with that reference standard. And it’s not perfect,” Chiang says. “Be we thought it was better than anything else out there that we’re aware of.”

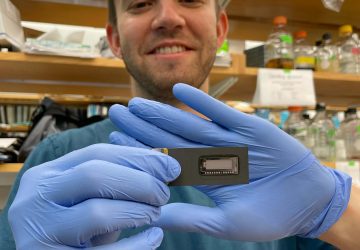

Then Chiang and his team ran a study that looked at the accuracy of telemedicine diagnoses and live exams independently. Instead of comparing them to each other, they compared them with the new reference standard.

They focused on infants with retinopathy of prematurity, which is the leading cause of blindness in preemie babies. The disease can be diagnosed by examining the patterns of certain structures in the eye, either by looking through a magnifying device that shines a light into the baby’s dilated eye, or by studying images taken by a wide-angle ophthalmic camera.

The result: Telemedicine exams were just as good as live exams in the study. But there’s one caveat: In cases where there was a minor level of disease—usually on the periphery of the eye—the live exam more often caught it. Chiang hypothesizes that either the cameras did not perfectly capture structures at the periphery, or that examiners saw something that wasn’t actually there.

It’s not the most satisfying result. “Telemedicine works pretty well for diagnosing eye disease, but neither a real eye exam nor telemedicine is perfect,” says Chiang.

The advantage of telemedicine, however, is that it gives people a way to connect with the right experts. Patients can have their images sent to certain specialists, rather than being stuck with the examiner who happens to work nearby. “Who does your exam matters more than what method they use,” Chiang says.