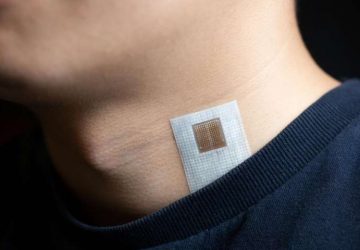

An average person with type 1 diabetes and no insulin pump sticks a needle into their abdomen between 700 and 1,000 times per year. A person with the hormone disorder acromegaly travels to a doctor’s office to receive a painful injection into the muscles of the butt once a month. Someone with multiple sclerosis may inject the disease-slowing interferon beta drug three times per week, varying the injection site among the arms, legs and back.

Medical inventor Mir Imran, holder of more than 400 patents, spent the last seven years working on an alternate way to deliver large drug molecules like these, and his solution—an unusual “robotic” pill—was recently tested in humans.

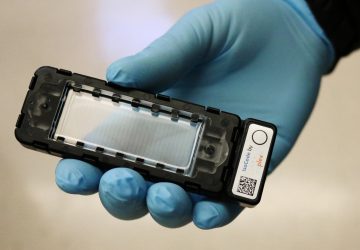

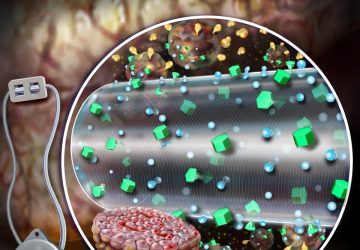

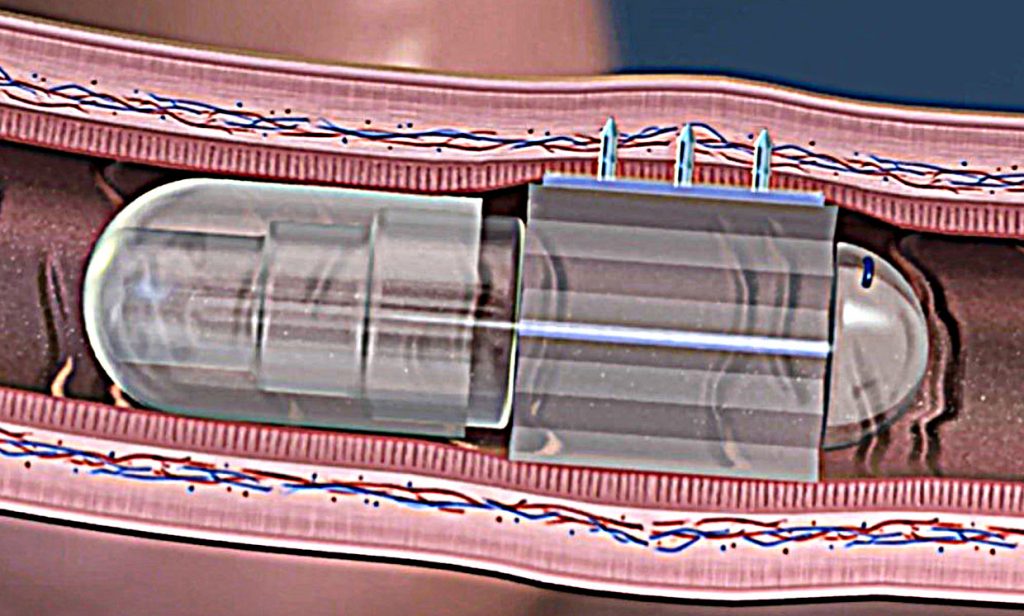

The RaniPill capsule works like a miniature Rube Goldberg device: Once swallowed, the capsule travels to the intestines where the shell dissolves to mix two chemicals to inflate a balloon to push out a needle to pierce the intestinal wall to deliver a drug into the bloodstream.

Simple, right?

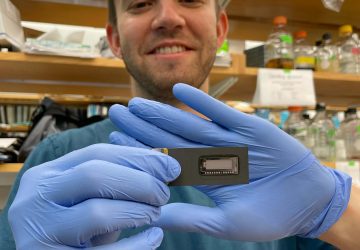

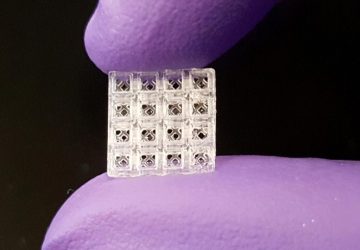

It may not be simple, but so far, it’s working: Imran’s company, San Jose-based Rani Therapeutics, just announced the successful completion of the first human study of the pill—a 20-person trial that showed a drug-free version of the capsule (roughly the size of a fish oil pill) was well-tolerated, easy-to-swallow, and passed safely through the stomach and intestines.

“There were no issues in swallowing the capsule, in passing it out, and, most importantly, no sensation when the balloon inflated and deflated,” says Imran, Rani’s chairman and CEO.

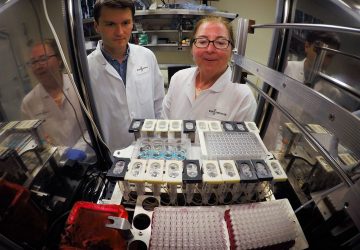

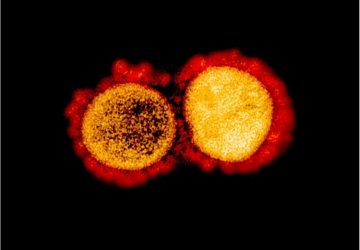

The human trial follows more than 100 animal studies testing over 1,000 capsules filled with all types of large-molecule drugs, such as insulin and Humira, according to the company.

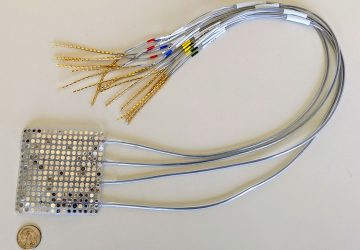

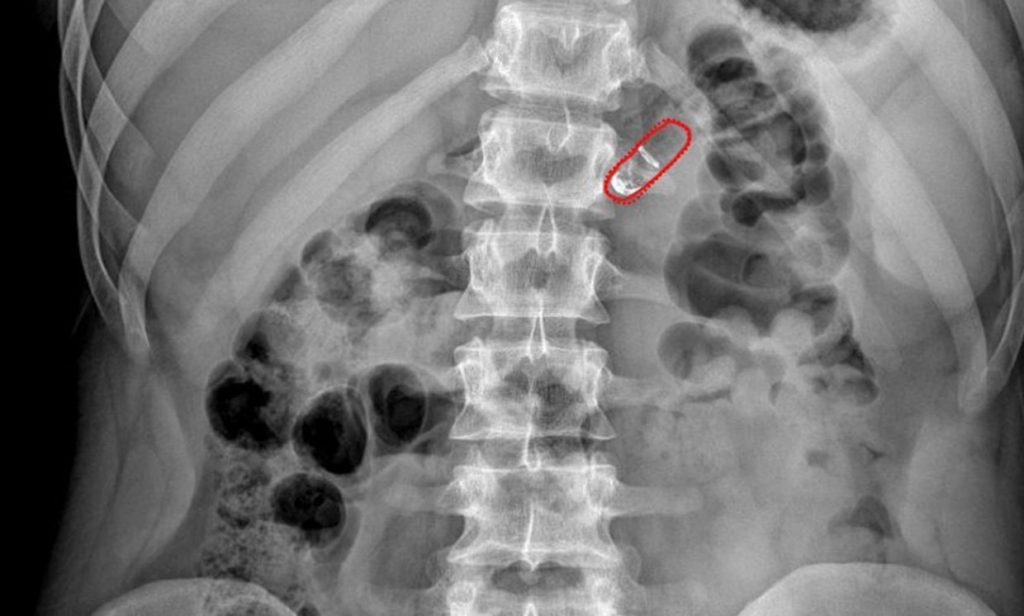

The RaniPill capsule (outlined in red), moving from the stomach to the intestines.

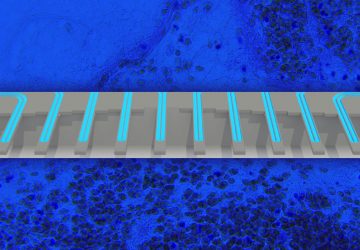

Working from the outside in, the RaniPill consists of a special coating that protects the pill from the stomach’s acidic juices. Then, as the pill is pushed into the intestines and pH levels rise to about 6.5, the coating dissolves to reveal a deflated biocompatible polymer balloon.

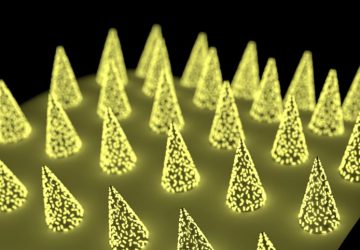

Upon exposure to the intestinal environment, a tiny pinch point made of sugar inside the balloon dissolves, causing two chemicals trapped on either side of the pinch point to mix and produce carbon dioxide. That gas inflates the balloon, and the pressure of the inflating balloon pushes a dissolvable microneedle filled with a drug of choice into the wall of the intestines. Human intestines lack sharp pain receptors, so the micro-shot is painless.

The intestinal wall does, however, have lots and lots of blood vessels, so the drug is quickly taken up into the bloodstream, according to the company’s animal studies. The needle itself dissolves.

The recent human study did not include a drug-filled needle, but the next one, scheduled to begin this year, will include a needle filled with a drug called octreotide for individuals with the hormone disorder acromegaly.

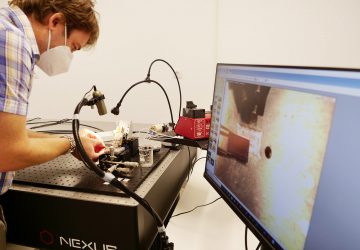

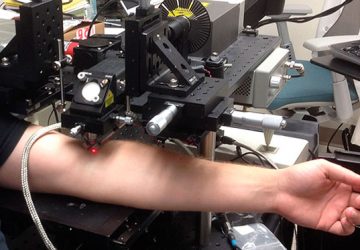

The current study included 10 individuals who ate prior to swallowing the capsule and 10 that fasted. After swallowing the capsule, participants were free to walk around and behave normally, and they paused every 30 minutes to have an X-ray taken to track the progress of the capsule.

Subjects said the pill was easy to swallow, according to Imran, who says he has personally swallowed “quite a few,” including without water. Food did not seem to impact the pill’s performance other than taking a little longer to get through the stomach of the individuals who had eaten. Participants passed the remnants of the balloon within 1-4 days.

Imran calls the device a robot though it has no electrical parts and no metal. “Even though it has no brains and no electronics, it

[works through]

an interplay between material science and the chemistry of the body,” says Imran. “It performs a single mechanical function autonomously.”

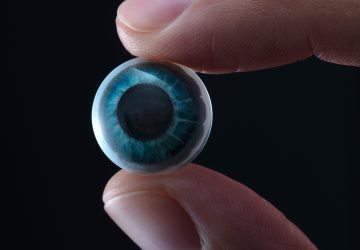

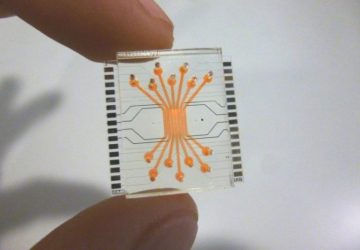

For the next version of the RaniPill capsule, Imran and his team are developing tiny wireless sensors for the part of the balloon that pushes the microneedle into the intestinal wall. When applied, the sensors could send a wireless signal that the drug has been delivered, allowing doctors to monitor patient compliance and patients to receive a text message if they miss a dose.

Rani Therapeutics has partnerships with Novartis and Shire, just acquired by Takeda Pharmaceuticals, to test the delivery of various drugs using the platform.

Source : www.spectrum.ieee.org